A Simple Strategy for Persistent, Non-Correlated Returns

A simple strategy of buying the worst-performing stocks of the previous 12 months and holding them for 12 months has outperformed Japan’s Topix index by an average of 7% annually for the past 9 years with low correlation to the underlying index. These returns are based on 100% out-of-sample tests and are robust across multiple starting dates.

The strategy suffered a maximum drawdown of 12% (relative to the index) and only one other drawdown in excess of 5%. Both of these drawdowns were caused by unprecedented natural disasters that led to significant liquidation of the Tokyo market. In both cases, the strategy underperformed AFTER the events that led to this liquidation, so it is at least possible that an active manager could avoid significant drawdowns if a similar event were to happen again.

Why The Turnaround Strategy Keeps on Delivering

During the past 20 years, the median earnings of the top 800 stocks in the Tokyo market grew at about 6% annually, which is about the same as that of the MSCI global index during the same period. In any given year, by definition, half of the company’s underperform the median and half outperform. Since analysts need to explain the reason for this underperformance, there is always pressure on them to explain in terms of secular, permanent weaknesses that will make investors want to sell the stocks even after they are down.

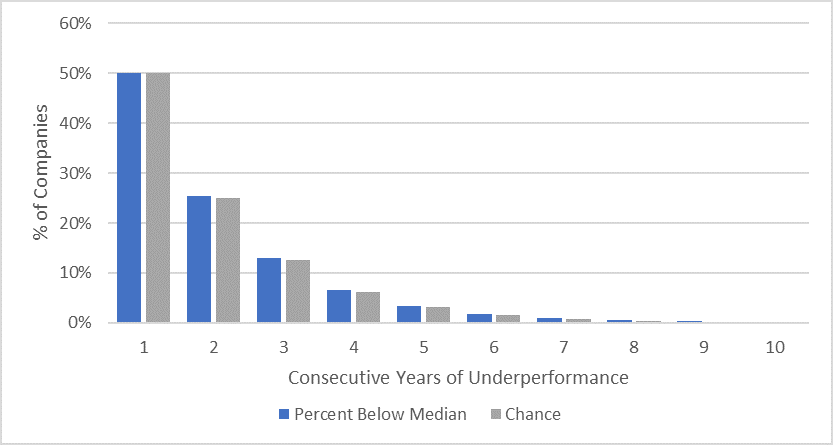

As it turns out, though, it is very unusual for any company’s earnings to underperform the median for two consecutive years. Chart 2, below, shows that the odds of any stock underperforming in two consecutive year is 25.4%, only 40bps higher than would be the case if you simply flipped a coin 1,600 times. Bad earnings in one year do not lead to bad earnings in the following year any more often than would be the case if earnings were driven by a random coin flip. The odds that any company would ever suffer three consecutive below-median growth is only 13%, again, no different than would be the case if driven by a random coin flip.

Persistence of EPS Underperformance

However, the inverse of this strategy, shorting the best 40 performers of the previous year, does not add value, even though the earnings growth of the best performing companies is subject to the same mean reversion tendency of the earnings underperformers. The reason that a reverse turnaround strategy doesn’t work is entirely a function of investor psychology. We haven’t tried this on other markets, so it may in fact be a function of Japanese investor psychology. Whatever the case, investors in the Japanese market appear to consistently over-react to bad news, while reacting more rationally to good news. Put another way, the market accurately predicts the mean reversion of companies with superior growth but consistently and inaccurately predicts the continuation of inferior growth.

One reason that Japanese stocks might over-react to bad news more consistently than to good news is that Japanese research firms are chronically understaffed. A typical analyst in Japan might cover twice as many companies as her Western counterpart and might have less than half the level of assistance from associate analysts and clerical staff. The result, in my opinion, is that Japanese analysts concentrate even more of their time on the better performing stocks in their coverage and subject the underperforming stocks to much deeper states of neglect than would be the case in most Western markets. While the higher scrutiny received by the better performing stocks doesn’t always prevent them from becoming over-valued, it’s easy to see how neglect in the underperforming segment can lead to more consistent mispricing.

Another possible reason is the inherent conservativeness of Japanese managers. Contrary to popular belief, Japanese managers have never been oblivious to their obligations to shareholders; it’s just that they tend to believe that these obligation are at best equal, if not secondary to their obligations to employees and suppliers. One of the manifestations of this approach is that they tend to put a lot more emphasis on sustainability than on return, and are often under-levered. This is especially true of companies that are struggling at the operational level. Of the 40 stocks that most recently fit our worst-performer criteria, a third of them had cash on the balance sheet in excess of total liabilities while those who had net liabilities, on average, had annual cash flow from operations equivalent to 80% of total net liabilities. In almost any scenario, it’s nearly impossible for companies with this much financial flexibility to fail in the traditional sense, and even if they did, Japanese banks and suppliers have traditionally gone to extraordinary lengths to help keep troubled companies afloat. This means that almost every company that ever gets into trouble is given enough time and support they need to recover and prosper again. Exceptions to this rule of thumb make for riveting headlines, but statistically, they are rare.

Managing the Volatility

Truth be told, even a strategy that worked in every one of the past 20 years could still stop working at any time for any reason. And a blind adherence to this simple, mechanical stock picking approach did not outperform in every year. Declines in relative performance were especially pronounced exactly when the market declines were most pronounced, making it an especially difficult strategy for human beings, whose judgement is clouded by emotion. I started the Tokyo Turnaround Letter to focus on fundamental and quantitative research techniques and strategies to help navigate the issues that haunt the turnaround investor.

Fundamental Analysis

You don’t have to buy every stock on the list. Unlike a lot of deep-value based strategies, the turnaround anomaly does not depend on a small number of phenomenally performing stocks to compensate for otherwise sub-par performance. For example, a well-known book/price anomaly buys the cheapest stocks in the universe on the basis of price to book. Most of the stocks in a portfolio following this strategy will underperform the index, but thanks to inclusion of a small number of spectacularly performing stocks, the portfolio in aggregate outperforms. To take advantage of this anomaly, you have to buy every stock that appears in the screen to ensure that you own all of these winners. Otherwise, you are most likely to end up with a collection of really bad investments.

The turnaround strategy doesn’t work like that at all. If you choose any stock from the screened list, there is about a 60% chance that the ones you pick will outperform the median stock, which is a lot better than the 50% chance you would take by choosing from the entire market. Returns are distributed in an almost normal bell-curve, except that they are slightly skewed to the upside. Positive relative returns of more than 50% exceed negative relative returns of more than 50%. Positive relative returns of between 25% and 50% exceed negative relative returns of the same magnitude. Positive relative returns of between 1% and 25% exceed negative relative returns of the same magnitude. If you are just an average stock picker, you have a better chance of picking winners from this universe than you would if you chose from the entire universe of Japanese listed companies.

Survivorship bias

Our data suffers from a slight survivorship bias. We collected prices and fundamental data for the top 800 companies by market capital as of the end of October 2022. Only 564 of these companies had data for all 20 years, so each year in the survey, the universe from which we were choosing stocks expanded by about 1% annually. This doesn’t necessarily mean that the 1% of stocks that were replaced would necessarily have altered our results. We don’t know this.

We have checked the bankruptcy databases for the past 10 years and discovered no bankruptcies or business discontinuations of any company that would have been large enough to be part of our screening database. To a certain extent, the size factor is a built-in protection, but this doesn’t eliminate the possibility that a few stocks could have been selected for investment multiple years before their eventual failure, and this would have hurt performance. In the worst-case scenario, however, it is impossible for survivorship bias to have had cumulative effect of more than 1% annually.

Fortunately, there is a simple solution. We don’t have to buy stocks with any financial risks. The most important element in the fundamental analysis of any turnaround is financial flexibility. Companies that have operating problems need to have financial strength to give them time to turn-around their operations. This is what the turnaround letter does best: We conduct a thorough check of a company’s financial strength, including forensic tests for fraudulent overstatement of assets and understatement of liabilities before we comment or write about any stock. During times when Azabu Research anticipates an unusual level of macro-economic stress, this screen for financial strength becomes more rigorous, and in times when robust economic growth is anticipated, the tolerance for risk rises. This fundamental analysis of the financial strength of companies with depressed operating performance might be the most important thing we do. This subjective part of the process isn’t back tested, but we have more than 30 years of experience in applying this process. On average, we predicted seven of every six bankruptcies that actually occurred during this time, so we are highly confident that our process will protect investors.

Simple Timing Enhancements

In back-tests, we simulated purchases of stocks all on the same day, immediately after they were identified as being among the worst performers for the previous year. On average, it turns out that about 12 months is the most optimal period to measure both the period of underperformance and the expected holding period, but for any given trade, there is no reason to insist on such uniformity. Stocks underperform for different reasons and recover at their own pace.

Some of the most egregious drawdowns of a purely mechanical turnaround strategy occur when the period of underperformance simply takes longer to complete than normal. These times appear to be surprisingly easy to predict. The simple use of moving averages to delay entry points can significantly reduce the major drawdowns of this strategy.

When applying technical filters, though, we step outside of the boundaries of rigorous statistical analysis and begin to implement artistic license. So be it. We are not suggesting that technical analysis form the basis of an investment decision; only that such tools, if used carefully, may improve the timing of entry and exit points, especially when dealing with complete changes in direction that we are dealing with in the turnaround strategy.

We prefer a parabolic system, which is effectively a moving average in which the speed of the moving average increases over time. The more time that passes, the more sensitive that such a system becomes, so that as a stock declines, the moving average increases in speed and eventually catches up to the stock. This approach almost automatically avoids the most spectacular drawdowns and prevents you from missing out on most of the more violent rebounds.

When Recovery is Immediate

It is important to measure the moving average of the relative performance and not the absolute performance since many of the strategy’s relative drawdowns occur during periods of strong market performance. If you use a technical trigger mechanism based on absolute returns, you might find yourself buying a lot of stocks that go up, but nevertheless, underperform. In the long run, that will hurt you.

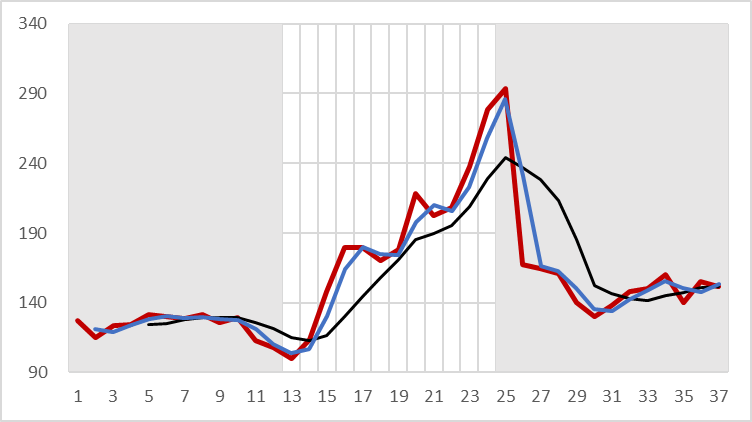

Chart 4, shows an example of a stock that underperformed the market by 21% in the year to 10/12, then outperformed by 194% in the subsequent 12 months. In this case, the rebound was immediate, and there was no need to wait. In this case, a parabolic trading system confirmed the rebound within weeks of the quantitative trading signal and captured nearly 100% of the expected model return.

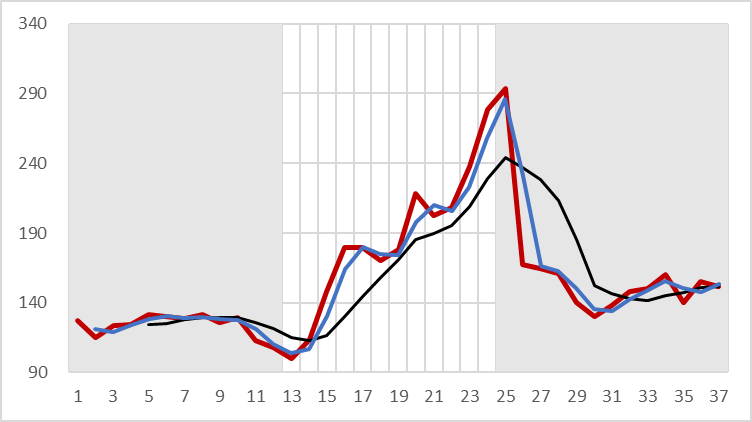

In contrast to the above example, chart 5, below, shows a stock that underperformed the market by 32% in they year to 10/19, and subsequently underperformed by another 38% before bottoming out about 6 month later. A parabolic trading system, in which began with a 80-day moving average and accelerated to a 40-day moving average, triggered a buy signal mid-April of the following year, enabling a 50% return in only 6 months, instead of suffering a 6% loss that would have been incurred if held from October to October.

When Recovery is Delayed